|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

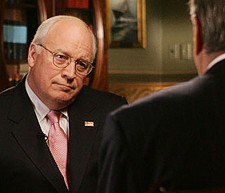

Don't Wait For Bad News Every day is a chance to introduce the upland lifestyle to the wider world. If you're reading this, then you probably bumped into Upland Life somewhat indirectly. Most likely you were using a web search engine, like Google, while bird-dogging some obscure bit of wingshooting trivia, or saw a link in an online forum or e-mail from a buddy. At least, that's what we would have assumed up until early 2006. For better or worse, we can probably thank Vice President Cheney for at least a modest change in our web site traffic patterns. First, it seems safe to say that everyone who has ever swung a shotgun in the field instantly winced on reading the news of his quail hunting accident. Which of us has never, even once, felt that hot rush of shame when we inadvertently threw some birdshot closer than we would have liked to the truck, the dog, the barn, the utility pole, or a buddy's blaze orange cap barely sticking out of the cover 20 yards away? It's easy to be pious about this sort of thing, especially when you've had the good fortune to have never come close to what turns out, in retrospect, to have been a less-than-safe shot. You know your cousin's brother-in-law Chuck, right? He has the uncanny ability to hear a sneaky pheasant's two cold feet running through a hedgerow before your Springer can even catch a whiff of it. But when you're standing right next to him shouting "hen!" or "too low!" at the top of your lungs, all his adrenaline lets him hear is, "your shot, Chuck!" Or your good old gramps, who expertly took endless rabbits and prairie chickens to (literally) flesh out his family's meager diet during the Great Depression, and has forgotten more about bird hunting than you'll ever know… but whose macular degeneration makes him a menace an hour before sunset (whether he's driving or shooting). We've all got a list of people we'll forgive, at least a couple of times, for even their life-threatening transgressions. This editor's grandfather carried some of his buddy's #6 shot in his scalp for the second half of his life, but kept the buddy for just as long.

Even so, many of us have seen that fortunately rare jackass in the field that earns only scorn for bad manners, recklessness with a shotgun, and the obtuseness that filters out even the least subtle attempts to straighten him out. That jackass's worst quality, though, is his inability to recognize the alarm his behavior causes, and his unwillingness to show remorse. Only exile from gun-carrying social circles is adequate for someone that cannot abstractly imagine himself on the dangerous end of the weapon he carries (or of the truck he drives) and amend his ways. Cheney's lapse in the field obviously struck him to the core, and whatever impact that will have on his future days in the field, the media craziness over the event propelled the words "quail hunting" farther into the national foreground than it has probably ever been. For about two weeks. We remind ourselves of these things because as often as a long-time hunting family grapples with them, the larger public (and the mainstream media – which presents so much of the world to those that don't personally experience much of it) doesn't even have the basic facts, let alone understand the nuances. So when an important political figure - especially one that the punditocracy loves to vilify - had his finger on the trigger in a hunting accident, all sorts of things happen, rarely good. It's been many moons, now, since that Texas mishap. The lawyer's bruises have gone down, the late night comedians have moved on to other fare, and most of us bird hunters have probably fallen back into our bad habit of not talking about our passion outside of our little corner of the culture. That recession, back into our comfort zone, is a critical mistake. Remember every conversation you had with non-hunters when that wounded lawyer was in the news? Whether or not you expressed sympathy or condemnation for Cheney, you were probably adamant in reminding others that you and your fellow hunters are very cautious in the field. That no one in your family has ever plucked pellets out of anything (or anyone) other than a bird headed for the table. That being in the field is about the fellowship, the dogs, fresh air, and the fall tall tales you'll be embellishing all summer long.

The Cheney accident was one of those relatively rare moments when hunting crosses over into mainstream news coverage. Here at Upland Life, we actually got a call from a USA Today reporter who had been tasked with writing an article about luxury hunting lodge destinations and the wealthy people that patronize them. Her editorial assignment was clumsily lumping high-end Rocky Mountain elk hunting operations, classy midwest pheasant lodges, and antebellum southern quail locales into the sort of singular, muddled mess that only ignorance can conceive. We had quite the couple of telephone conversations, and took the opportunity to help her shape her coverage and focus on just one sliver of the larger hunting landscape. Before we knew it, she was off to the first class Rio Piedra Plantation in Camilla, Georgia, and doing a pretty nice job writing about her positive experience there. But if not for her lengthy talk with us, and with several other people willing to invest some time in tuning her into the complexities of the topic, her article might have been much less helpful. We talked to her after her trip, and when asked for her impressions of plantation quail hunting, her very first reaction was, "The dogs! I just couldn't believe the dogs."

-UL |

||||||||||||||

|

^Top | Home | About UplandLife.com | Contact Us | Advertising/Listings | Privacy / Policies | Site Map Entire contents copyright © 2026 UplandLife.com, All Rights Reserved. Content Technology From NorseCode. |

No clay pigeons' feelings were hurt during this introduction to Sporting Clays

at

No clay pigeons' feelings were hurt during this introduction to Sporting Clays

at  If you didn't see the print edition, Laura Bly's USA Today article, from March 2, 2006, is

still

If you didn't see the print edition, Laura Bly's USA Today article, from March 2, 2006, is

still